The Wild World of Ants

“True warfare in which large rival armies fight to the death is known only in man and in social insects.”

Richard Dawkins, The Selfish Gene

Our passing familiarity with ants prevents us from understanding what a bizarre and fascinating world they live in. It’s a world of forever wars, strange behaviors, and genetics completely different from our own.

The truth about ants is that even sci-fi writers would have had a hard time coming up with the reality they inhabit.

Below is a playlist of ant-appreciation. It’s a collection of podcasts, videos, and excerpts from a book that will leave you in awe of these little critters that dominate the world on a small scale.

Ologies: Myrmecology (ANTS) with Terry McGlynn [podcast]

If you have never listened to Ologies, this is a great episode to sell you on the show. Host Alie Ward is a science communicator who interviews various scientists and she is a delight to listen to. Her signature move is to cut in with asides via post-production in order to provide more context around the topic at hand. These are always informative and funny. This episode with an ant expert is a perfect entrance into the wild world of ants. You’ll learn:

The biggest enemy for most ants are other colonies of the same species.

Argentine ants are an invasive species that have completely taken over the Los Angeles, CA area. They have a super colony hundreds of miles in size, which is small compared to the one in South America. Learn more in the Kurzgesagt video below.

Ants communicate with chemicals and we don’t fully understand how it all works.

A dying ant releases a chemical that causes other ants to drag them into the “dead pile”. If a scientist brushes this chemical on a healthy ant, their comrades will still drag them into the pile.

All worker ants are female. Almost all the boys have wings and their job is "to have sex and then die".

Most army ants species are specialists at attacking and eating other social insect colonies. See the other Kurzgesagt video below for more.

The queen is the captive in the situation. The sisters are more related to each other than queen is to the daughter. Ant relatedness is fascinating and find more details in The Selfish Gene section below.

Ants keep gardens! Leaf cutter ants tend to fungus gardens in much the same way we tend to farms.

Ants farm other species! Some ants will grow aphids and milk them for honeydew and use ranching management techniques similar to what humans do.

Ants sometimes find themselves in a death spiral, where the chemical path gets lost and they all follow each other in a circle until they die.

The best way to deal with ants in your home is to simply let them eat the food they find, follow them back to the hole they came through, and then caulk it.

Getting bitten by a bullet ant on the finger is like hitting your finger with a hammer as hard as you can.

Kurzgesagt: The World War of the Ants—The Army Ant [video]

Kurzgesagt has mastered the art of short educational videos with amazing visuals. This video showcases the intensity and devastation of the army ant. You’ll learn:

Ants evolved 160 million years ago.

There are around 10,000 species of ants.

There are around 10 quadrillion individual ants, or ten thousand trillion, or 1.25 million per human.

Facts about the army ant:

There are 200 species in the genus Eciton.

They don't build nests and are nomadic.

A large swarm can kill 500,000 things in one day.

They overwhelm their enemies with sheer numbers.

Army ants don’t fight each other, even other groups. This is different than most ants.

Leaf cutter ants form some of the most complicated social structures in the world and have several classes of specialized ants, including soldiers that can hold their own again army ant swarms.

Kurzgesagt: The Billion Ant Mega Colony and the Biggest War on Earth [video]

This title is no hyperbole. Ants REALLY like to war with each other, and there are continuous battles for land happening across the planet. The scale has increased in modern times because of the super colonies, which are made possible by us accidentally seeding invasive species everywhere. You’ll learn:

Linepithema humile is the humble but extremely successful Argentine ant.

They are smaller than fire ants and army ants but they specialize in being adaptable and growing massive colonies.

There is about one queen per 160 workers, which is a lot of queens.

They started spreading outside their native lands in the late 1800’s because of human migration and trade. Numerous competing colonies kept each other at bay, but once a few queens made it to new lands, there was no competition and they were able to grow as one continuous colony.

Different colonies will fight each other, so if you can take an ant from one place in California and move it 200 miles away and it fits right in, they are by definition part of the same colony.

Argentine ants have quickly replaced 90% of California native ants.

Red imported fire ants are now taking over in the Southeastern US and are giving Argentine ants a run for their money as a competing invasive species.

Smarter Every Day: How to get Ants to carry a sign [video]

A short video that peaks inside the complexity of leaf cutter ants in the Amazon Rainforest. Watching thousands march in line at night with pieces of green attached to their back, while even smaller ants clean the leaf along the way is a sight to behold. You’ll learn:

Leaf cutter ants forage for sodium.

This means that if you would like to have one carry a little sign for you, just pee a little on it. For science of course.

These are the ants with some of the most complex social structures besides humans and have little fungus gardens they tend to.

Science Vs: Ants—Tales from the Underground [podcast]

Two stories about ants from the Science Vs podcast. You’ll learn:

How adaptable ants are. There is a story of thousands of ants continuously falling into a nuclear bunker with nothing in it. A make-shift colony survived for years without a queen or food source. Well, there was a food source, it just happened to be the steady supply of new ants falling into the bunker.

Matabele ants will go back and save each other if wounded. As one more example of just how different the ant way of life is, if an ant is severely wounded they won’t signal for help because it would be too much of a burden.

The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins [chapter 10 of the book]

The main thing to know about The Selfish Gene is its thesis that organisms (including us) don’t use our genes to reproduce, but that genes use US to reproduce themselves. All life is a replication mechanism for genes, not the other way around. The whole book is a detailed argument for why this is true.

There are many surprising things to be learned from Dawkins in this book, but I found chapter 10 about social insects to be among the most fascinating.

For one, the bizarre behavior and complicated social structure of many ant species can be explained by the fact that the workers are sterile.

“The majority of individuals in a social insect colony are sterile workers. The ‘germ line’—the line of immortal gene continuity—flows through the bodies of a minority of individuals, the reproductives. These are the analogues of our own reproductive cells in our testes and ovaries. The sterile workers are the analogy of our liver, muscle, and nerve cells.”

Workers are literally disposable.

“The death of a single sterile worker bee is no more serious to its genes than is the shedding of a leaf in autumn to the genes of a tree.”

The genetic relatedness of a typical ant colony is completely different than how we intuitively understand relatedness.

This is worth breaking down a little further because it is a crucial point in why ants are unique. Below is a reminder on how human reproduction works:

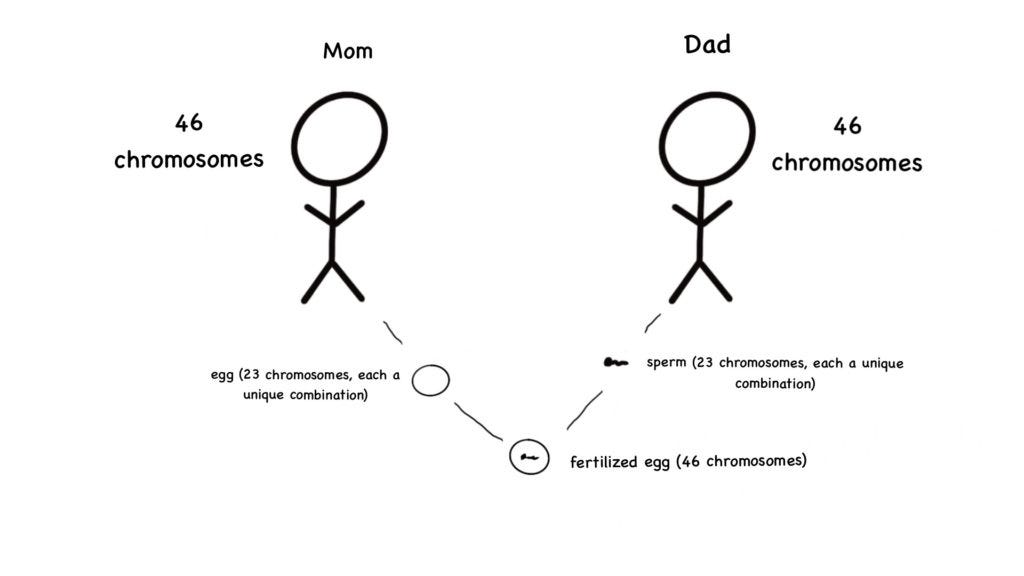

We have 46 chromosomes, which is really two full sets of our DNA (the full instructions for how to make a human is contained within 23 chromosomes). One set came from our mom, and one from our dad.

Let's picture one set of chromosomes from Mom as 1a, 2a, all the way to 23a, and then the set of chromosomes from Dad as 1b all the way to 23b. If the gene for eye color is on chromosome 9, we'll have two versions of this gene (9a and 9b). The one that wins out in expressing itself in our appearance is the dominant gene. This is the dominant and recessive matrix we learned about in school with the peas.

When we produce our own sex cells (sperm or egg), each is a unique combination of one set of DNA. We would take our 9a and 9b, combine them in a new way, and then that would become our version of 9a that would be partnered with someone else's newly formed 9b. This is what happens with meiosis and then fertilization.

This allows for a great amount of genetic variability, but also predictable relatedness. Kids and parents share half their genes, and siblings also share half their genes.

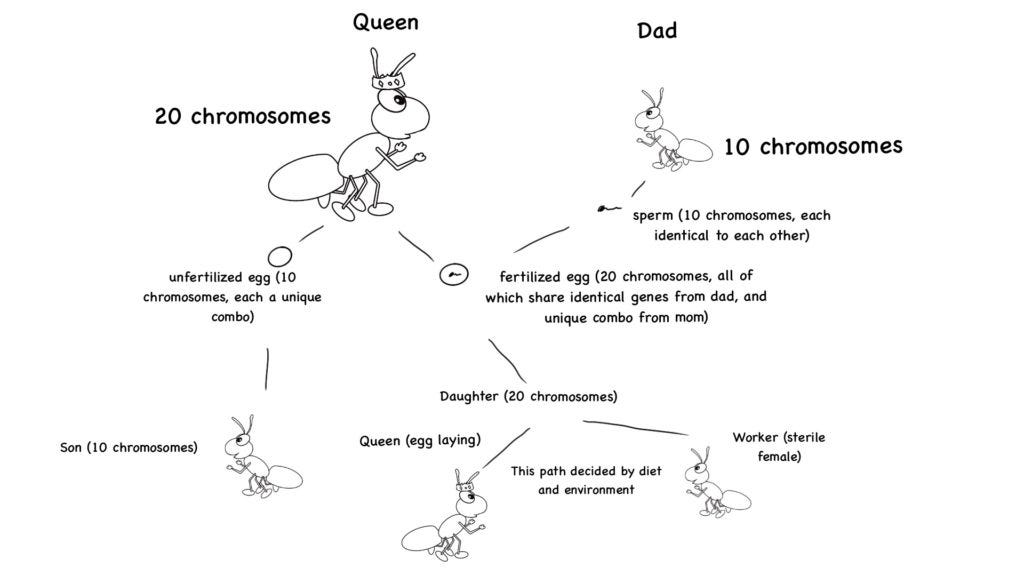

And this is how it all works for ants:

This is a completely different set up, and leads to some interesting outcomes. I'll let Dawkins unpack what the above diagram means.

“A hymenopteran [social insect] nest typically has only one mature queen. She made one mating flight when young and stored up the sperms for the rest of her long life—ten years or even longer. She rations the sperms out to her eggs over the years, allowing the eggs to be fertilized as they pass out through her tubes. But not all the eggs are fertilized. The unfertilized ones develop into males. A male therefore has no father, and all the cells of his body contain just a single set of chromosomes (all obtained from his mother) instead of a double set (one from the father and one from the mother) as in ourselves. In terms of the analogy of Chapter 3, a male hymenopteran has only one copy of each ‘volume’ in each of his cells, instead of the usual two. A female hymenopteran, on the other hand, is normal in that she does have a father, and she has the usual double set of chromosomes in each of her body cells. Whether a female develops into a worker or a queen depends not on her genes but on how she is brought up. That is to say, each female has a complete set of queen-making genes, and a complete set of worker-making genes (or, rather, sets of genes for making each specialized caste of worker, soldier, etc.). Which set of genes is ‘turned on’ depends on how the female is reared, in particular on the food she receives.”

Male ants have no fathers. This might lead to some awkward conversations.

Another consequence of how ants reproduce is that sister ants are all half-identical to each other. This means that male ants and the queen are half related to each other (the queen's unfertilized egg that turns into a male is a random assortment of half her genes), the queen and daughters are half related to each other, and sisters are actually three-quarters related to each other.

This is why scientists believe that workers are in charge of an ant colony, not the queen. The workers are more related to each other than they are to the queen, and are genetically motivated to use the queen to make more of themselves.

“A gene for vicariously making sisters replicates itself more rapidly than a gene for making offspring directly. Hence worker sterility evolved. It is presumably no accident that true sociality, with worker sterility, seems to have evolved no fewer than eleven times independently in the Hymenoptera and only once in the whole of the rest of the animal kingdom, namely in the termites.”

This notion of thousands of sisters forcing their mom to give them more siblings is maybe the most shocking thing I learned about the ant world.

The truth is stranger than fiction

It's no wonder so many sci-fi writers use ants and other social insects as inspiration for their aliens. The xenomorphs from the Alien franchise comes immediately to mind. But honestly, the more I learn about social insects, the more I would rather deal with what a sci-fi author dreams up than being shrunk down and dropped in an ant colony.